Bhopal disaster

The Bhopal disaster (also referred to as the Bhopal gas tragedy) is the world's worst industrial catastrophe. It occurred on the night of December 2–3, 1984 at the Union Carbide India Limited (UCIL) pesticide plant in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. UCIL was the Indian subsidiary of Union Carbide Corporation (UCC). Indian Government controlled banks and the Indian public held a 49.1 percent ownership share. In 1994, the Supreme Court of India allowed UCC to sell its 50.9 percent share. The Bhopal plant was sold to McLeod Russel (India) Ltd. UCC is now a subsidiary of Dow Chemical Company. A leak of methyl isocyanate (MIC) gas and other chemicals from the plant resulted in the exposure of several thousands of people. Estimates vary on the death toll. The official immediate death toll was 2,259 and the government of Madhya Pradesh has confirmed a total of 3,787 deaths related to the gas release.[1] Other government agencies estimate 15,000 deaths.[2] Others estimate that 8,000 died within the first weeks and that another 8,000 have since died from gas-related diseases.[3][4] A government affidavit in 2006 stated the leak caused 558,125 injuries including 38,478 temporary partial and ~3900 severely and permanently disabling injuries.[5]

Chemicals abandoned at the plant continue to leak and pollute the groundwater.[6][7][8] Whether the chemicals pose a health hazard is disputed.[2]

Civil and criminal cases are pending in the United States District Court, Manhattan and the District Court of Bhopal, India, involvng UCC, UCIL employees, and Warren Anderson, UCC CEO at the time of the disaster.[9][10] In June 2010, seven ex-employees, including the former UCIL chairman, were convicted in Bhopal of causing death by negligence and sentenced to two years imprisonment and a fine of about $2,000 each, the maximum punishment allowed by law. An eighth former employee was also convicted but died before judgment was passed.[11]

Summary of background and causes

The UCIL factory was built in 1969 to produce the pesticide Sevin (UCC's brand name for carbaryl) using methyl isocyanate (MIC) as an intermediate. A MIC production plant was added in 1979.[12][13][14]

During the night of December 2–3, 1984, water entered a tank containing 42 tons of MIC. The resulting exothermic reaction increased the temperature inside the tank to over 200 °C (392 °F) and raised the pressure. The tank vented releasing toxic gases into the atmosphere. The gases were blown by northwesterly winds over Bhopal.

Theories of how the water entered the tank differ. At the time, workers were cleaning out a clogged pipe with water about 400 feet from the tank. The operators assumed that owing to bad maintenance and leaking valves, it was possible for the water to leak into the tank.[15] However, this water entry route could not be reproduced.[16] UCC also maintains that this route was not possible, but instead alleges water was introduced directly into the tank as an act of sabotage by a disgruntled worker via a connection to a missing pressure gauge on the top of the tank. Early the next morning, a UCIL manager asked the instrument engineer to replace the gauge. UCIL's investigation team found no evidence of the necessary connection; however, the investigation was totally controlled by the government denying UCC investigators access to the tank or interviews with the operators.[17][18] The 1985 reports give a picture of what led to the disaster and how it developed, although they differ in details.[18][19][20]

Factors leading to the magnitude of the gas leak include:

- Storing MIC in large tanks and filling beyond recommended levels

- Poor maintenance after the plant ceased MIC production at the end of 1984

- Failure of several safety systems (due to poor maintenance)

- Safety systems being switched off to save money—including the MIC tank refrigeration system which could have mitigated the disaster severity

The problem was made worse by the mushrooming of slums in the vicinity of the plant, non-existent catastrophe plans, and shortcomings in health care and socio-economic rehabilitation.[3][4][21]

Public information

Much speculation arose in the aftermath. The closing of the plant to outsiders (including UCC) by the Indian government and the failure to make data public contributed to the confusion. The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) were forbidden to publish their data on health effects until after 1994. The initial investigation was conducted entirely by CSIR and the Central Bureau of Investigation.[4]

Plant production process

UCC produced carbaryl using MIC as an intermediate.[4] After the Bhopal plant was built, other manufacturers including Bayer produced carbaryl without MIC, though at a greater manufacturing cost.[22] However, Bayer also uses the UCC process at the chemical plant once owned by UCC at Institute, West Virginia, USA.

Contributing factors

Other factors identified by the inquiry included: use of a more dangerous pesticide manufacturing method, large-scale MIC storage, plant location close to a densely populated area, undersized safety devices, and the dependence on manual operations.[4]

Plant management deficiencies were also identified - lack of skilled operators, reduction of safety management, insufficient maintenance, and inadequate emergency action plans.[4][23]

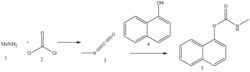

The chemical process, or "route", used in the Bhopal plant reacted methylamine with phosgene to form MIC (methyl isocyanate), which was then reacted with 1-naphthol to form the final product, carbaryl. This route differed from MIC-free routes used elsewhere, in which the same raw materials are combined in a different manufacturing order, with phosgene first reacted with the naphthol to form a chloroformate ester, which is then reacted with methyl amine. In the early 1980s, the demand for pesticides had fallen, but production continued, leading to buildup of stores of unused MIC.[4][22]

Work conditions

Attempts to reduce expenses affected the factory's employees and their conditions. Kurzman argues that "cuts ... meant less stringent quality control and thus looser safety rules. A pipe leaked? Don't replace it, employees said they were told ... MIC workers needed more training? They could do with less. Promotions were halted, seriously affecting employee morale and driving some of the most skilled ... elsewhere".[24] Workers were forced to use English manuals, even though only a few had a grasp of the language.[15][25]

By 1984, only six of the original twelve operators were still working with MIC and the number of supervisory personnel was also cut in half. No maintenance supervisor was placed on the night shift and instrument readings were taken every two hours, rather than the previous and required one-hour readings.[15][24] Workers made complaints about the cuts through their union but were ignored. One employee was fired after going on a 15-day hunger strike. 70% of the plant's employees were fined before the disaster for refusing to deviate from the proper safety regulations under pressure from management.[15][24]

In addition, some observers, such as those writing in the Trade Environmental Database (TED) Case Studies as part of the Mandala Project from American University, have pointed to "serious communication problems and management gaps between Union Carbide and its Indian operation", characterised by "the parent companies [sic] hands-off approach to its overseas operation" and "cross-cultural barriers".[26] The personnel management policy led to an exodus of skilled personnel to better and safer jobs.

Equipment and safety regulations

- It emerged in 1998, during civil action suits in India, that, unlike Union Carbide plants in the US, its Indian subsidiary plants were not prepared for problems. No action plans had been established to cope with incidents of this magnitude. This included not informing local authorities of the quantities or dangers of chemicals used and manufactured at Bhopal.[3][4][15][22]

- The MIC tank alarms had not worked for four years.[3][4][15][27]

- There was only one manual back-up system, compared to a four-stage system used in the US.[3][4][15][27]

- The flare tower and the vent gas scrubber had been out of service for five months before the disaster. The gas scrubber therefore did not treat escaping gases with sodium hydroxide (caustic soda), which might have brought the concentration down to a safe level.[27] Even if the scrubber had been working, according to Weir, investigations in the aftermath of the disaster discovered that the maximum pressure it could handle was only one-quarter of that which was present in the accident. Furthermore, the flare tower itself was improperly designed and could only hold one-quarter of the volume of gas that was leaked in 1984.[3][4][15][28]

- To reduce energy costs, the refrigeration system, designed to inhibit the volatilization of MIC, had been left idle—the MIC was kept at 20 degrees Celsius (room temperature), not the 4.5 degrees advised by the manual, and some of the coolant was being used elsewhere.[3][4][15][27]

- The steam boiler, intended to clean the pipes, was out of action for unknown reasons.[3][4][15][27]

- Slip-blind plates that would have prevented water from pipes being cleaned from leaking into the MIC tanks through faulty valves were not installed. Their installation had been omitted from the cleaning checklist.[3][4][15]

- The water pressure was too weak to spray the escaping gases from the stack. They could not spray high enough to reduce the concentration of escaping gas.[3][4][15][27]

- According to the operators the pressure gauge of MIC tank had been malfunctioning for roughly a week. Other tanks had been used for that week, rather than repairing the broken one, which was left to "stew". The build-up in temperature and pressure is believed to have affected the magnitude of the gas release.[3][4][15][27] UCC investigation studies have disputed this hypothesis. Actually on the night of the incident when it was discovered that water entered the tank, the operators managed to transfer one ton of MIC to the reaction vessel by pressurizing tank 610 hoping to alleviate the problem.

- Carbon steel valves were used at the factory, even though they corrode when exposed to acid.[22] On the night of the disaster, a leaking carbon steel valve was found, allowing water to enter the MIC tanks. The pipe was not repaired because it was believed it would take too much time and be too expensive.[3][4][15][27]

- UCC admitted in their own investigation report that most of the safety systems were not functioning on the night of December 3, 1984.[19]

- Themistocles D'Silva asserts in the latest book—The Black Box of Bhopal—that the design of the MIC plant, following government guidelines, was "Indianized" by UCIL engineers to maximize the use of indigenous materials and products. It also dispensed with the use of sophisticated instrumentation as not appropriate for the Indian plant. Because of the unavailability of electronic parts in India, the Indian engineers preferred pneumatic instrumentation. This is supported with original government documents, which are appended. In a letter from the Ministry of Petroleum and Chemicals, No. A&I-26(1)/70, dated 13 March, 1972 to UCIL, it specified that, Approved/Registered Indian Engineering Design and Consultancy Organizations must be the prime consultants and builders. UCIL, in reply, letter dated November 24, 1972, informed that 6 Indian design and production engineers would be associated from the very beginning of the design and engineering work of the project, to maximize indigenous capability in the interest of the country. Reputable Indian firms - Larson and Toubro constructed the MIC storage tanks and Taylor of India Ltd. installed the associated instruments. Hence,contrary to the public perception the Bhopal MIC storage tanks, although constructed of required quality stainless steel, they were not identical as the ones in USA. When built, the Bhopal plant had met all the standards set by Indian Standards Institutions and was in compliance with the National Electrical Code and other government regulations. The book also discredits the unproven allegations in the CSIR Report. More importantly, the supposedly malfunctioning pressure valve on tank 610 somehow did work on the night of December 3, as a ton of MIC was transferred to the reaction vessel when the problem was discovered. This finding was only uncovered after the analysis of the tank residue by UCC investigators.[29]

History/Previous warnings and accidents

A series of prior warnings and MIC-related accidents had occurred:

- In 1976, the two trade unions reacted because of pollution within the plant.[4][23]

- In 1981, a worker was splashed with phosgene. In panic he ripped off his mask, thus inhaling a large amount of phosgene gas; he died 72 hours later.[4][23]

- In January 1982, there was a phosgene leak, when 24 workers were exposed and had to be admitted to hospital. None of the workers had been ordered to wear protective masks.

- In February 1982, an MIC leak affected 18 workers.[4][23]

- In August 1982, a chemical engineer came into contact with liquid MIC, resulting in burns over 30 percent of his body.[4][23]

- In September 1982, a Bhopal journalist, Raajkumar Keswani, started writing his prophetic warnings of a disaster in local weekly 'Rapat'. Headlines, one after another ' Save, please save this city', 'Bhopal sitting at the top of a volcano' and 'if you don't understand, you will all be wiped out' were not paid any heed.[30]

- In October 1982, there was a leak of MIC, methylcarbaryl chloride, chloroform and hydrochloric acid. In attempting to stop the leak, the MIC supervisor suffered intensive chemical burns and two other workers were severely exposed to the gases.[4][23]

- During 1983 and 1984, leaks of the following substances regularly took place in the MIC plant: MIC, chlorine, monomethylamine, phosgene, and carbon tetrachloride, sometimes in combination.[4][23]

- Reports issued months before the incident by scientists within the Union Carbide corporation warned of the possibility of an accident almost identical to that which occurred in Bhopal. The reports were ignored and never reached senior staff.[4][22]

- Union Carbide was warned by American experts who visited the plant after 1981 of the potential of a "runaway reaction" in the MIC storage tank; local Indian authorities warned the company of problems on several occasions from 1979 onwards. Again, these warnings were not heeded.[4][22]

The leakage

In November 1984, most of the safety systems were not functioning. Many valves and lines were in poor condition. Tank 610 contained 42 tons of MIC, much more than safety rules allowed.[4] During the nights of 2–3 December, a large amount of water entered tank 610. A runaway reaction started, which was accelerated by contaminants, high temperatures and other factors. The reaction generated a major increase in the temperature inside the tank to over 200 °C (400 °F). This forced the emergency venting of pressure from the MIC holding tank, releasing a large volume of toxic gases. The reaction was sped up by the presence of iron from corroding non-stainless steel pipelines.[4] It is known that workers cleaned pipelines with water. They were not told by the supervisor to add a slip-blind water isolation plate. Because of this, and the bad maintenance, the workers consider it possible for water to have accidentally entered the MIC tank.[4][15] UCC maintains that a "disgruntled worker" deliberately connected a hose to a pressure gauge.[4][17]

Timeline, summary

At the plant[4]

- 21:00 Water cleaning of pipes starts.

- 22:00 Water enters tank 610, reaction starts.

- 22:30 Gases are emitted from the vent gas scrubber tower.

- 00:30 The large siren sounds and is turned off.

- 00:50 The siren is heard within the plant area. The workers escape.

Outside[4]

- 22:30 First sensations due to the gases are felt—suffocation, cough, burning eyes and vomiting.

- 1:00 Police are alerted. Residents of the area evacuate. Union Carbide director denies any leak.

- 2:00 The first people reached Hamidia Hospital. Symptoms include visual impairment and blindness, respiratory difficulties, frothing at the mouth, and vomiting.

- 2:10 The alarm is heard outside the plant.

- 4:00 The gases are brought under control.

- 7:00 A police loudspeaker broadcasts: "Everything is normal".

Health effects

Short term health effects

The leakage caused many short term health effects in the surrounding areas. Apart from MIC, the gas cloud may have contained phosgene, hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide, hydrogen chloride, oxides of nitrogen, monomethyl amine (MMA) and carbon dioxide, either produced in the storage tank or in the atmosphere.[4]

The gas cloud was composed mainly of materials denser than the surrounding air, stayed close to the ground and spread outwards through the surrounding community. The initial effects of exposure were coughing, vomiting, severe eye irritation and a feeling of suffocation. People awakened by these symptoms fled away from the plant. Those who ran inhaled more than those who had a vehicle to ride. Owing to their height, children and other people of shorter stature inhaled higher concentrations. Many people were trampled trying to escape.[4]

Thousands of people had succumbed by the morning hours. There were mass funerals and mass cremations as well as disposal of bodies in the Narmada river. 170,000 people were treated at hospitals and temporary dispensaries. 2,000 buffalo, goats, and other animals were collected and buried. Within a few days, leaves on trees yellowed and fell off. Supplies, including food, became scarce owing to suppliers' safety fears. Fishing was prohibited as well, which caused further supply shortages.[4]

A total of 36 wards were marked by the authorities as being "gas affected", affecting a population of 520,000. Of these, 200,000 were below 15 years of age, and 3,000 were pregnant women. In 1991, 3,928 deaths had been certified. Independent organizations recorded 8,000 dead in the first days. Other estimations vary between 10,000 and 30,000. Another 100,000 to 200,000 people are estimated to have permanent injuries of different degrees.[4]

The acute symptoms were burning in the respiratory tract and eyes, blepharospasm, breathlessness, stomach pains and vomiting. The causes of deaths were choking, reflexogenic circulatory collapse and pulmonary oedema. Findings during autopsies revealed changes not only in the lungs but also cerebral oedema, tubular necrosis of the kidneys, fatty degeneration of the liver and necrotising enteritis.[31] The stillbirth rate increased by up to 300% and neonatal mortality rate by 200%.[4]

Hydrogen cyanide debate

Whether hydrogen cyanide was present in the gas mixture is still a controversy.[31][32] Exposed at higher temperatures, MIC breaks down to hydrogen cyanide (HCN). According to Kulling and Lorin, at +200 °C, 3% of the gas is HCN.[33] However, according to another scientific publication,[34] MIC when heated in the gas-phase starts breaks down to hydrogen cyanide (HCN) and other products above 400 °C. Concentrations of 300 ppm can lead to immediate collapse.

Laboratory replication studies by CSIR and UCC scientists failed to detect any HCN or HCN-derived side products. Chemically, HCN is known to be very reactive with MIC.[35] HCN is also known to react with hydrochloric acid, ammonia, and methylamine (also produced in tank 610 during the vigorous reaction with water and chloroform) and also with itself under acidic conditions to form trimers of HCN called triazenes. None of the HCN-derived side products were detected in the tank residue.[36]

The non-toxic antidote sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) in intravenous injections increases the rate of conversion from cyanide to non-toxic thiocyanate. Treatment was suggested early, but because of confusion within the medical establishments, it was not used on larger scale until June 1985.[4]

Long term health effects

.jpg)

It is estimated that 20,000 have died since the accident from gas-related diseases. Another 100,000 to 200,000 people are estimated to have permanent injuries.[4]

The quality of the epidemiological and clinical research varies. Reported and studied symptoms are eye problems, respiratory difficulties, immune and neurological disorders, cardiac failure secondary to lung injury, female reproductive difficulties and birth defects among children born to affected women. Other symptoms and diseases are often ascribed to the gas exposure, but there is no good research supporting this.[4]

There is a clinic established by a group of survivors and activists known as Sambhavna. Sambhavna is the only clinic that will treat anybody affected by the gas, or the subsequent water poisoning, and treats the condition with a combination of Western and traditional Indian medicines, and has performed extensive research.[37]

Union Carbide as well as the Indian Government long denied permanent injuries by MIC and the other gases. In January 1994, the International Medical Commission on Bhopal (IMCB) visited Bhopal to investigate the health status among the survivors as well as the health care system and the socio-economic rehabilitation.

The reports from Indian Council of Medical Research[38] were not completely released until around 2003.

Aftermath of the leakage

- Medical staff were unprepared for the thousands of casualties.[4]

- Doctors and hospitals were not informed of proper treatment methods for MIC gas inhalation. They were told to simply give cough medicine and eye drops to their patients.[4]

- The gases immediately caused visible damage to the trees. Within a few days, all the leaves fell off.[4]

- 2,000 bloated animal carcasses had to be disposed of.[4]

- "Operation Faith": On December 16, the tanks 611 and 619 were emptied of the remaining MIC. This led to a second mass evacuation from Bhopal.[4]

- Complaints of a lack of information or misinformation were widespread. The Bhopal plant medical doctor did not have proper information about the properties of the gases. An Indian Government spokesman said that "Carbide is more interested in getting information from us than in helping our relief work."[4]

- As of 2008, UCC had not released information about the possible composition of the cloud.[4]

- Formal statements were issued that air, water, vegetation and foodstuffs were safe within the city. At the same time, people were informed that poultry was unaffected, but were warned not to consume fish.[4]

Compensation from Union Carbide

- The Government of India passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act that gave the government rights to represent all victims in or outside India.[4]

- UCC offered US $350 million, the insurance sum.[4] The Government of India claimed US$ 3.3 billion from UCC.[4] In 1999, a settlement was reached under which UCC agreed to pay US$470 million (the insurance sum, plus interest) in a full and final settlement of its civil and criminal liability.[4]

- When UCC wanted to sell its shares in UCIL, it was directed by the Supreme Court to finance a 500-bed hospital for the medical care of the survivors. Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre (BMHRC) was inaugurated in 1998. It was obliged to give free care for survivors for eight years.[4]

Economic rehabilitation

- After the accident, no one under the age of 18 was registered. The number of children exposed to the gases was at least 200,000.[4]

- Immediate relief was decided two days after the tragedy.[4]

- Relief measures commenced in 1985 when food was distributed for a short period and ration cards were distributed.[4]

- Widow pension of the rate of Rs 200/per month (later Rs 750) was provided.[4]

- One-time ex-gratia payment of Rs 1,500 to families with monthly income Rs 500 or less was decided.[4]

- Each claimant was to be categorised by a doctor. In court, the claimants were expected to prove "beyond reasonable doubt" that death or injury in each case was attributable to exposure. In 1992, 44 percent of the claimants still had to be medically examined.[4]

- From 1990 interim relief of Rs 200 was paid to everyone in the family who was born before the disaster.[4]

- The final compensation (including interim relief) for personal injury was for the majority Rs 25,000 (US$ 830). For death claim, the average sum paid out was Rs 62,000.[4]

- Effects of interim relief were more children sent to school, more money spent on treatment, more money spent on food, improvement of housing conditions.[4]

- The management of registration and distribution of relief showed many shortcomings.[39]

- In 2007, 1,029,517 cases were registered and decided. Number of awarded cases were 574,304 and number of rejected cases 455,213. Total compensation awarded was Rs.1,546.47 crores.[40]

- Because of the smallness of the sums paid and the denial of interest to the claimants, a sum as large as Rs 10 billion is expected to be left over after all claims have been settled.[4]

Occupational rehabilitation

- 33 of the 50 planned work-sheds for gas victims started. All except one was closed down by 1992.[4]

- 1986, the MP government invested in the Special Industrial Area Bhopal. 152 of the planned 200 work-sheds were built. In 2000, 16 were partially functioning.[4]

- It is estimated that 50,000 persons need alternative jobs, and that less than 100 gas victims have found regular employment under the government's scheme.[4]

Habitation rehabilitation

- 2,486 flats in two- and four-story buildings were constructed in the "Widows colony" outside Bhopal. The water did not reach the upper floors. It was not possible to keep cattle. Infrastructure like buses, schools, etc. were missing for at least a decade.[4]

Health care

- In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the health care system became tremendously overloaded. Within weeks, the State Government established a number of hospitals, clinics and mobile units in the gas-affected area.[4]

- Radical health groups set up JSK (the People's Health Centre) that was working a few years from 1985.[4]

- Since the leak, a very large number of private practitioners have opened in Bhopal. In the severely affected areas, nearly 70 percent do not appear to be professionally qualified.[4]

- The Government of India has focused primarily on increasing the hospital-based services for gas victims. Several hospitals have been built after the disaster. In 1994, there were approximately 1.25 beds per 1,000, compared to the recommendation from the World bank of 1.0 beds per 1,000 in developing countries.[4]

- The Bhopal Memorial Hospital and Research Centre (BMHRC) is a 350-bedded super speciality hospital. Heart surgery and hemodialysis are done. Major specialities missing are gynecology, obstetrics and pediatrics. Eight mini-units (outreach health centers) were started. Free health care for gas victims should be offered until 2006.[4] The management has faced problems with strikes, and the quality of the health care is disputed.[41][42][43]

- Sambhavna Trust is a charitable trust that registered in 1995. The clinic gives modern and Ayurvedic treatments to gas victims, free of charge.[4][44]

Environmental rehabilitation

- When the factory was closed in 1985–1986, pipes, drums and tanks were cleaned and sold. The MIC and the Sevin plants are still there, as are storages of different residues. Isolation material is falling down and spreading.[4]

- The area around the plant was used as a dumping area for hazardous chemicals. In 1982 tubewells in the vicinity of the UCC factory had to be abandoned.[4] UCC's laboratory tests in 1989 revealed that soil and water samples collected from near the factory and inside the plant were toxic to fish.[45] Several other studies has shown polluted soil and groundwater in the area.[4]

- Reported polluting compounds are, among others, naphthol, naphthalene, Sevin, tarry residue, mercury, toxic organochlorines, volatile organochlorine compounds, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, hexachloroethane, hexachlorobutadiene, pesticide HCH and halo-organics. It is plausible that these chemicals have some negative health effects on those exposed, but there is no scientific evidence.[4]

- In order to provide safe drinking water to the population around the UCC factory, there is a scheme for improvement of water supply.[40]

- In December 2008, the Madhya Pradesh High Court decided that the toxic waste should be incinerated at Ankleshwar in Gujarat.[46]

Union Carbide's defense

Now owned by Dow Chemical Company, Union Carbide denies allegations against it on its website dedicated to the tragedy. The corporation believes that the accident was the result of sabotage, stating that safety systems were in place and operative. It also stresses that it did all it could to alleviate human suffering following the disaster.[47]

Investigation into possible sabotage

Theories of how the water entered the tank differ. At the time, workers were cleaning out pipes with water. The workers maintain that entry of water through the plant's piping system during the washing of lines was possible because a slip-bind was not used, the downstream bleeder lines were partially clogged, many valves were leaking, and the tank was not pressurized. The water, which was not draining properly through the bleeder valves, may have built up in the pipe, rising high enough to pour back down through another series of lines in the MIC storage tank. Once water had accumulated to a height of 6 meters (20 feet), it could drain by gravity flow back into the system. Alternatively, the water may have been routed through another standby "jumper line" that had only recently been connected to the system. Indian scientists suggested that additional water might have been introduced as a "back-flow" from the defectively designed vent-gas scrubber.[4][15] However, none of these postulated routes of entry could be duplicated when tested by the Central Bureau of Investigators (CBI) and UCIL engineers. The company cites an investigation conducted by the engineering consulting firm Arthur D. Little, which concluded that a single employee secretly and deliberately introduced a large amount of water into the MIC tank by removing a meter and connecting a water hose directly to the tank through the metering port.[17] Carbide claims such a large amount of water could not have found its way into the tank by accident, and safety systems were not designed to deal with intentional sabotage. Documents cited in the Arthur D. Little Report state that the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) along with UCIL engineers tried to simulate the water-washing hypothesis as a route of the entry of water into the tank. This all-important test failed to support this as a route of water entry. UCC claims the plant staff falsified numerous records to distance themselves from the incident, and that the Indian Government impeded its investigation and declined to prosecute the employee responsible, presumably because that would weaken its allegations of negligence by Union Carbide.[48]

Safety and equipment issues

The corporation denies the claim that the valves on the tank were malfunctioning, claiming that "documented evidence gathered after the incident showed that the valve close to the plant's water-washing operation was closed and leak-tight. Furthermore, process safety systems—in place and operational—would have prevented water from entering the tank by accident". Carbide states that the safety concerns identified in 1982 were all allayed before 1984 and "none of them had anything to do with the incident".[49]

The company admits that "the safety systems in place could not have prevented a chemical reaction of this magnitude from causing a leak". According to Carbide, "in designing the plant's safety systems, a chemical reaction of this magnitude was not factored in" because "the tank's gas storage system was designed to automatically prevent such a large amount of water from being inadvertently introduced into the system" and "process safety systems—in place and operational—would have prevented water from entering the tank by accident". Instead, they claim that "employee sabotage—not faulty design or operation—was the cause of the tragedy".[49]

Response

The company stresses the "immediate action" taken after the disaster and their continued commitment to helping the victims. On December 4, the day following the leak, Union Carbide sent material aid and several international medical experts to assist the medical facilities in Bhopal.[49]

Union Carbide states on its website that it put $2 million into the Indian Prime Minister's immediate disaster relief fund on 11 December 1984.[49] The corporation established the Employees' Bhopal Relief Fund in February 1985, which raised more than $5 million for immediate relief.[50]

According to Union Carbide, in August 1987, they made an additional $4.6 million in humanitarian interim relief available.[50]

Union Carbide states that it also undertook several steps to provide continuing aid to the victims of the Bhopal disaster after the court ruling, including:

- The sale of its 50.9 percent interest in UCIL in April 1992 and establishment of a charitable trust to contribute to the building of a local hospital. The sale was finalized in November 1994. The hospital was begun in October 1995 and was opened in 2001. The company provided a fund with around $90 million from sale of its UCIL stock. In 1991, the trust had amounted approximately $100 million. The hospital caters for the treatment of heart, lung and eye problems.[47]

- Providing "a $2.2 million grant to Arizona State University to establish a vocational-technical center in Bhopal, which was constructed and opened, but was later closed and leveled by the government".[51]

- Donating $5 million to the Indian Red Cross.[51]

- Developing the Responsible Care system with other members of the chemical industry as a response to the Bhopal crisis, which is designed "to help prevent such an event in the future by improving community awareness, emergency preparedness and process safety standards".[50]

Long-term fallout

Legal action against Union Carbide has dominated the aftermath of the disaster. However, other issues have also continued to develop. These include the problems of ongoing contamination, criticisms of the clean-up operation undertaken by Union Carbide, and a 2004 hoax.

Legal action against Union Carbide

Legal proceedings involving UCC, the United States and Indian governments, local Bhopal authorities, and the disaster victims started immediately after the catastrophe.

Legal proceedings leading to the settlement

On 14 December 1984, the Chairman and CEO of Union Carbide, Warren Anderson, addressed the US Congress, stressing the company's "commitment to safety" and promising to ensure that a similar accident "cannot happen again". However, the Indian Government passed the Bhopal Gas Leak Act in March 1985, allowing the Government of India to act as the legal representative for victims of the disaster,[50] leading to the beginning of legal wrangling.

In 1985, Henry Waxman, a Californian Democrat, called for a US government inquiry into the Bhopal disaster, which resulting in US legislation regarding the accidental release of toxic chemicals in the United States.[52]

March 1986 saw Union Carbide propose a settlement figure, endorsed by plaintiffs' US attorneys, of $350 million that would, according to the company, "generate a fund for Bhopal victims of between $500–600 million over 20 years". In May, litigation was transferred from the US to Indian courts by US District Court Judge. Following an appeal of this decision, the US Court of Appeals affirmed the transfer, judging, in January 1987, that UCIL was a "separate entity, owned, managed and operated exclusively by Indian citizens in India".[50] The judge in the US granted UCC's forum request, thus moving the case to India. This meant that, under US federal law, the company had to submit to Indian jurisdiction.

Litigation continued in India during 1988. The Government of India claimed US$ 350 million from UCC.[4] The Indian Supreme Court told both sides to come to an agreement and "start with a clean slate" in November 1988.[50] Eventually, in an out-of-court settlement reached in 1989, Union Carbide agreed to pay US$ 470 million for damages caused in the Bhopal disaster, 15% of the original $3 billion claimed in the lawsuit.[4] By the end of October 2003, according to the Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department, compensation had been awarded to 554,895 people for injuries received and 15,310 survivors of those killed. The average amount to families of the dead was $2,200.[53]

Throughout 1990, the Indian Supreme Court heard appeals against the settlement from "activist petitions". In October 1991, the Supreme Court upheld the original $470 million, dismissing any other outstanding petitions that challenged the original decision. The Court ordered the Indian government "to purchase, out of settlement fund, a group medical insurance policy to cover 100,000 persons who may later develop symptoms" and cover any shortfall in the settlement fund. It also requested UCC and its subsidiary "voluntarily" fund a hospital in Bhopal, at an estimated $17 million, to specifically treat victims of the Bhopal disaster. The company agreed to this.[50]

Charges against Warren Anderson and others

UCC Chairman and CEO Warren Anderson was arrested and released on bail by the Madhya Pradesh Police in Bhopal on December 7, 1984. The arrest, which took place at the airport, ensured Anderson would meet no harm by the Bhopal community. Anderson was taken to UCC's house after which he was released six hours later on $2,100 bail and flown out on a government plane. In 1987, the Indian government summoned Anderson, eight other executives and two company affiliates with homicide charges to appear in Indian court.[54] Union Carbide balked, saying the company is not under Indian jurisdiction.[54]

In 1991, local Bhopal authorities charged Anderson, who had retired in 1986, with manslaughter, a crime that carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. He was declared a fugitive from justice by the Chief Judicial Magistrate of Bhopal on February 1, 1992, for failing to appear at the court hearings in a culpable homicide case in which he was named the chief defendant. Orders were passed to the Government of India to press for an extradition from the United States.

The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal of the decision of the lower federal courts in October 1993, meaning that victims of the Bhopal disaster could not seek damages in a US court.[50]

In 2004, the Indian Supreme Court ordered the Indian government to release any remaining settlement funds to victims. In September 2006, the Welfare Commission for Bhopal Gas Victims announced that all original compensation claims and revised petitions had been "cleared".[50]

In 2006, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York City uphold the dismissal of remaining claims in the case of Bano v. Union Carbide Corporation. This move blocked plaintiffs' motions for class certification and claims for property damages and remediation. In the view of UCC, "the ruling reaffirms UCC's long-held positions and finally puts to rest—both procedurally and substantively—the issues raised in the class action complaint first filed against Union Carbide in 1999 by Haseena Bi and several organizations representing the residents of Bhopal".

In June 2010, seven former employees of the Union Carbide subsidiary, all Indian nationals and many in their 70s, were convicted of causing death by negligence and each sentenced to two years imprisonment and fined Rs.1 lakh (US$2,124).[55] All were released on bail shortly after the verdict. The names of those convicted are: Keshub Mahindra, former non-executive chairman of Union Carbide India Limited; V.P. Gokhale, managing director; Kishore Kamdar, vice-president; J. Mukund, works manager; S.P. Chowdhury, production manager; K.V. Shetty, plant superintendent; and S.I. Qureshi, production assistant Federal class action litigation, Sahu v. Union Carbide et al. is presently pending on appeal before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York.[56] The litigation seeks damages for personal injury, medical monitoring[57] and injunctive relief in the form of cleanup[58] of the drinking water supplies[59] for residential areas near the Bhopal plant. A related complaint seeking similar relief for property damage claimants is stayed pending the outcome of the Sahu appeal before the federal district court in the Southern District of New York.

Changes in corporate identity

Sale of Union Carbide India Limited

Union Carbide sold its Indian subsidiary, which had operated the Bhopal plant, to Eveready Industries India Limited, in 1994.

Acquisition of Union Carbide by Dow Chemical Company

The Dow Chemical Company purchased Union Carbide in 2001 for $10.3 billion in stock and debt. Dow has publicly stated several times that the Union Carbide settlement payments have already fulfilled Dow's financial responsibility for the disaster. However, Dow did not purchase UCC's Indian subsidiary, Union Carbide India. That was sold in 1994 and renamed Eveready Industries India limited

Some Dow stockholders filed suits to stop the acquisition, noting the outstanding liabilities for the Bhopal disaster.[60] The acquisition has gained criticism from the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal, as it is apparently "contrary to established merger law" in that "Dow denies any responsibility for Carbide's Bhopal liabilities". According to the Bhopal Medical Appeal, Carbide "remains liable for the environmental devastation" as environmental damage was not included in the 1989 settlement, despite ongoing contamination issues.[60]

In June 2010, commentators criticised the disparity between the handling of the Bhopal disaster and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill (BP).[61][62][63][64]

Ongoing contamination

The contamination in the site itself and the surrounding areas did not arise directly from the Bhopal disaster, but rather from the materials processed at the plant and the conditions under which those materials were processed. The area around the plant was used as a dumping ground area for hazardous chemicals. Between 1969 and 1977, all effluents were dumped in an open pit. From then on, neutralization with hydrochloric acid was undertaken. The effluents went to two evaporation ponds. In the rainy seasons, the effluents used to overflow. It is also said that large quantities of chemicals are buried in the ground.[4]

By 1982 tubewells in the vicinity of the UCC factory had to be abandoned. In 1991 the municipal authorities declared water from over 100 tubewells to be unfit for drinking.[4]

Carbide's laboratory tests in 1989 revealed that soil and water samples collected from near the factory were toxic to fish. Twenty-one areas inside the plant were reported to be highly polluted. In 1994 it was reported that 21% of the factory premises were seriously contaminated with chemicals.[45][65][66]

Studies made by Greenpeace and others from soil, groundwater, wellwater and vegetables from the residential areas around UCIL and from the UCIL factory area show contamination with a range of toxic heavy metals and chemical compounds.[65][66][67][68][69]

Substances found, according to the reports, are naphthol, naphthalene, Sevin, tarry residues, alpha naphthol, mercury, organochlorines, chromium, copper, nickel, lead, hexachlorethane, Hexachlorobutadiene, pesticide HCH (BHC), volatile organic compounds and halo-organics. Many of these contaminants were also found in breast milk.

In 2002, an inquiry found a number of toxins, including mercury, lead, 1,3,5 trichlorobenzene, dichloromethane and chloroform, in nursing women's breast milk. Well water and groundwater tests conducted in the surrounding areas in 1999 showed mercury levels to be at "20,000 and 6 million times" higher than expected levels; heavy metals and organochlorines were present in the soil. Chemicals that have been linked to various forms of cancer were also discovered, as well as trichloroethene, known to impair fetal development, at 50 times above safety limits specified by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).[60]

In an investigation broadcast on BBC Radio 5 on November 14, 2004,[70] it was reported that the site is still contaminated with 'thousands' of metric tons of toxic chemicals, including benzene hexachloride and mercury, held in open containers or loose on the ground. A sample of drinking water from a well near the site had levels of contamination 500 times higher than the maximum limits recommended by the World Health Organization.[71]

In 2009, a day before the 25th anniversary of the disaster, Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), a Delhi based pollution monitoring lab, released latest tests from a study showing that groundwater in areas even three km from the factory up to 38.6 times more pesticides than Indian standards. [72]

The BBC took a water sample from a frequently used hand pump, located just north of the plant. The sample, tested in UK, was found to contain 1000 times the World Health Organization's recommended maximum amount of carbon tetrachloride, a carcinogenic toxin.[73] This shows that the ground water has been contaminated due to toxins leaking from the factory site.

Criticisms of clean-up operations

Lack of political willpower has led to a stalemate on the issue of cleaning up the plant and its environs of hundreds of tonnes of toxic waste, which has been left untouched. Environmentalists have warned that the waste is a potential minefield in the heart of the city, and the resulting contamination may lead to decades of slow poisoning, and diseases affecting the nervous system, liver and kidneys in humans. According to activists, there are studies showing that the rates of cancer and other ailments are high in the region.[74] Activists have demanded that Dow clean up this toxic waste, and have pressed the government of India to demand more money from Dow.

Carbide states that "after the incident, UCIL began clean-up work at the site under the direction of Indian central and state government authorities", which was continued after 1994 by the successor to UCIL, Eveready Industries, until 1998, when it was placed under the authority of the Madhya Pradesh Government.[50] Critics of the clean-up undertaken by Carbide, such as the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal, claim that "several internal studies" by the corporation, which evidenced "severe contamination", were not made public; the Indian authorities were also refused access. They believe that Union Carbide "continued directing operations" in Bhopal until "at least 1995" through Hayaran, the U.S.-trained site manager, even after the sale of its UCIL stock. The successor, Eveready Industries, abruptly relinquished the site lease to one department of the State Government while being supervised by another department on an extensive clean up program. The Madhya Pradesh authorities have announced that they will "pursue both Dow and Eveready" to conduct the clean-up as joint tortfeasors.

The International Campaign view Carbide's sale of UCIL in 1994 as a strategy "to escape the Indian courts, who threatened Carbide's assets due to their non-appearance in the criminal case". The successor, Eveready Industries India, Limited (EIIL), ended its 99-year lease in 1998 and turned over control of the site to the state government of Madhya Pradesh.[47] Currently, the Madhya Pradesh Government is trying to legally force Dow and EIIL to finance clean-up operations.

On 7 March 2009, Indian scientists of the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) have decided to investigate the long term health effects of the disaster. Studies will also be conducted to see if the toxic gases caused genetic disorders, low birth weight, growth and development disorders, congenital malformation and biological markers of MIC/toxic gas exposure.[75]

Settlement fund hoax

On December 3, 2004, the twentieth anniversary of the disaster, a man claiming to be a Dow representative named Jude Finisterra was interviewed on BBC World News. He claimed that the company had agreed to clean up the site and compensate those harmed in the incident, by liquidating Union Carbide for $12 billion USD.[76]

Immediately afterward, Dow's share price fell 4.2% in 23 minutes, for a loss of $2 billion in market value. Dow quickly issued a statement saying that they had no employee by that name—that he was an impostor, not affiliated with Dow, and that his claims were a hoax. The BBC broadcast a correction and an apology. The statement was widely carried.[77]

"Jude Finisterra" was actually Andy Bichlbaum, a member of the activist prankster group The Yes Men. In 2002, The Yes Men issued a fake press release explaining why Dow refused to take responsibility for the disaster and started up a website, at "DowEthics.com", designed to look like the real Dow website but with what they felt was a more accurate cast on the events. In 2004, a producer for the BBC emailed them through the website requesting an interview, which they gladly obliged.[78]

Taking credit for the prank in an interview on Democracy Now!, Bichlbaum explains how his fake name was derived: "Jude is the patron saint of impossible causes and Finisterra means the end of the Earth". He explained that he settled on this approach (taking responsibility) because it would show people precisely how Dow could help the situation as well as likely garnering major media attention in the US, which had largely ignored the disaster's anniversaries, when Dow attempted to correct the statement.[79]

After the original interview was revealed as a hoax, Bichlbaum appeared in a follow-up interview on the United Kingdom's Channel 4 News.[80] During the interview he was repeatedly asked if he had considered the emotions and reaction of the people of Bhopal when producing the hoax. According to the interviewer, "there were many people in tears" upon having learned of the hoax. Each time, Bichlbaum said that, in comparison, what distress he had caused the people was minimal to that for which Dow was responsible. In the 2009 film The Yes Men Fix the World, the Yes Men travel to Bhopal to assess public opinion on their prank, and are surprised to find that the residents applaud their efforts to bring responsibility to the corporate world.

2010 update

On June 7, eight UCIL executives including former chairman Keshub Mahindra were convicted of criminal negligence and sentenced to two years in jail. The sentences are under appeal.[81]

On June 24, the Union Cabinet of the Government of India approved a Rs1265cr aid package. It will be funded by Indian taxpayers through the government.[82]

On August 19, the US warned that renewal of Bhopal case to bring justice may have a chilling effect on US investment relationship.[83]

On August 20, the United States said that the Bhopal gas tragedy is a closed case now [84][85]

See also

- List of industrial disasters

- Corporate social responsibility

- Students for Bhopal

Notes

- ↑ http://www.mp.gov.in/bgtrrdmp/relief.htm

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Industrial Disaster Still Haunts India – South and Central Asia – msnbc.com". http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/34247132/ns/world_news-south_and_central_asia/page/2/. Retrieved December 3, 2009.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 Eckerman (2001) (see "References" below).

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 4.26 4.27 4.28 4.29 4.30 4.31 4.32 4.33 4.34 4.35 4.36 4.37 4.38 4.39 4.40 4.41 4.42 4.43 4.44 4.45 4.46 4.47 4.48 4.49 4.50 4.51 4.52 4.53 4.54 4.55 4.56 4.57 4.58 4.59 4.60 4.61 4.62 4.63 4.64 4.65 4.66 4.67 4.68 4.69 4.70 4.71 4.72 4.73 4.74 4.75 4.76 4.77 4.78 4.79 4.80 Eckerman (2004) (see "References" below).

- ↑ AK Dubey (21 June 2010). First14 News. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5qmWBEWcb. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ "No takers for Bhopal toxic waste". BBC. 2008-09-30. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7569891.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ Broughton, Edward (2005). "The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: a review". Environmental Health 4 (6): 6. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-4-6. PMID 15882472. PMC 1142333. http://www.ehjournal.net/content/4/1/6.

- ↑ Chander, J. (2001). "Water contamination: a legacy of the union carbide disaster in Bhopal, India". Int J Occup Environ Health 7 (1): 72–3. PMID 11210017. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11210017.

- ↑ "Company Defends Chief in Bhopal Disaster". New York Times. 2009-08-03. http://dealbook.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/03/company-defends-chief-in-bhopal-disaster/. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "U.S. Exec Arrest Sought in Bhopal Disaster". CBS News. 2009-07-31. http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/07/31/world/main5201155.shtml.

- ↑ "Bhopal trial: Eight convicted over India gas disaster". BBC News. 2010-06-07. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/south_asia/8725140.stm. Retrieved 2010-06-07.

- ↑ UCC manual (1976).

- ↑ UCC manual (1978).

- ↑ UCC manual (1979).

- ↑ 15.00 15.01 15.02 15.03 15.04 15.05 15.06 15.07 15.08 15.09 15.10 15.11 15.12 15.13 15.14 15.15 Chouhan et al. (2004).

- ↑ Steven R. Weisman. "Bhopal a Year Later: An Eerie Silence". The New York Times. p. 5.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Kalelkar (1988).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Trade Union Report (1985).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 UCC Investigation Report (1985).

- ↑ Varadarajan (1985).

- ↑ Eckerman (2005) (see "References" below).

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Kovel (2002).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 Eckerman (2006) (see "References" below).

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Kurzman (1987).

- ↑ Cassels (1983).

- ↑ TED case 233 (1997).

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 27.6 27.7 Lepowski (1994).

- ↑ Weir (1987).

- ↑ D'Silva, The Black Box of Bhopal (2006).

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Sriramachari (2004).

- ↑ Gassert TH, Dhara VR, (2005).

- ↑ Kulling and Lorin (1987).

- ↑ P.G. Blake and S. Ijadi-Maghsoodi, Kinetics and Mechanism of Thermal Decomposition of Methyl Isocyanate, International Journal of Chemical Kinetics, vol.14, (1982), pp. 945–952.

- ↑ K.H. Slotta, R. Tschesche, Berichte, vol.60, 1927, p.1031.

- ↑ Christoph Grundmann, Alfred Kreutzberger, J. Am. Chem. Soc., vol. 76, 1954, pp. 5646–5650.

- ↑ Bhopal.org

- ↑ Bhopal Gas Disaster Research Centre (2003?).

- ↑ Singh (2008).

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief and Rehabilitation Department". 2008-12-05. http://www.mp.gov.in/bgtrrdmp/.

- ↑ Bhopal Memorial Hospital closed indefinitely The Hindu 4.7.2005.

- ↑ Bhopal Memorial Hospital Trust(2001).

- ↑ Sick Berth Down to Earth (26.10.2008).

- ↑ "The Bhopal Medical appeal". Sambhavna Trust. http://www.bhopal.org.htm.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 UCC (1989).

- ↑ "Carbide waste to go: HC". 16 December 2008. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/India/Carbide_waste_to_go_HC/articleshow/3847412.cms. Retrieved 2009-01-07.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 "Statement of Union Carbide Corporation Regarding the Bhopal Tragedy". Bhopal Information Center, UCC. http://www.bhopal.com/ucs.htm.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Bhopal Information Center. Union Carbide Corporation. November 2009. http://www.bhopal.com/faq.htm. Retrieved 4 April 2010. "The Indian authorities are well aware of the identity of the employee [who sabotaged the plant] and the nature of the evidence against him. Indian authorities refused to pursue this individual because they, as litigants, were not interested in proving that anyone other than Union Carbide was to blame for the tragedy."

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 "Frequently Asked Questions". Bhopal Information Center, UCC. http://www.bhopal.com/faq.htm.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 50.6 50.7 50.8 50.9 "Chronology". Bhopal Information Center, UCC. November 2006. http://www.bhopal.com/chrono.htm.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "Incident Response and Settlement". Bhopal Information Center, UCC. http://www.bhopal.com/irs.htm.

- ↑ Dipankar De Sarkar (22 June 2010). "BP, Bhopal and the humble Indian brinjal". Hindustan Times. http://www.hindustantimes.com/BP-Bhopal-and-the-humble-Indian-brinjal/Article1-561254.aspx. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ Broughton (2005).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "India Acts in Carbide Case". The New York Times. May 17, 1988. p. D15. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DE0D71F3CF934A25756C0A96E948260.

- ↑ 8 Cr. Case No. 8460/1996

- ↑ http://www.bhopal.net/pdfs/Sahu%20Opinion%2011.3.08.pdf

- ↑ The Truth About Dow: Govt handling of Bhopal: Blot on Indian Democracy, 224 Indian groups tell PM.

- ↑ The Truth About Dow: 25 years on, Govt wakes up to Bhopal waste but can't find any one to clean it up.

- ↑ The Truth About Dow: Decades Later, Toxic Sludge Torments Bhopal.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 "What Happened in Bhopal?". The Bhopal Medical Appeal. http://www.bhopal.org/whathappened.html.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Krittivas (2010-06-17). "BP's $20 billion spill fund echoes in Bhopal justice cry". Reuters. http://in.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-49389220100617. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ Singh, Madhur (2010-06-08). "Bhopal, BP Oil Spill: Two Disasters, Different Justice". Time. TIME. http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1995029,00.html. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "BP is the company we all love to hate". Financial Times. 2010-06-18. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/9c732c98-7b01-11df-8935-00144feabdc0.html. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ Joan Smith (2010-06-20). "What about compensation for Bhopal?". The Independent (London: The Independant). http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/joan-smith/joan-smith-what-about-compensation-for-bhopal-2005296.html.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Labunska et al. (2003).

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Down to Earth (2003).

- ↑ Stringer et al. (2002).

- ↑ Srishti (2002).

- ↑ Peoples' Science Institute (2001).

- ↑ "Bhopal faces risk of 'poisoning'". BBC Radio 5. 2004-11-14. http://search.bbc.co.uk/cgi-bin/search/results.pl?scope=all&tab=av&recipe=all&q=bhopal+faces+risk+of+%27poisoning%27&x=0&y=0.

- ↑ "Bhopal 'faces risk of poisoning'". BBC Radio 5 website. 2004-11-14. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4010511.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ "Bhopal gas leak survivors still being poisoned: Study". Bhopal. 1 December 2009. http://www.cseindia.org/AboutUs/press_releases/press-20091201.htm.

- ↑ "Bhopal marks 25 years since gas leak devastation". BBC News. December 3, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8392206.stm. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ India's betrayal of Bhopal – Pamela Timms and Prabal KR Das, The Scotsman, November 22, 2007.

- ↑ 25 years on, study on Bhopal gas leak effects.

- ↑ video.

- ↑ Corporate Responsibility. 5 December 2004. Published by ZNet

- ↑ The Yes Men

- ↑ Democracy Now!

- ↑ video

- ↑ http://www.theistimes.com/tag/ucil/

- ↑ http://www.dnaindia.com/india/report_bhopal-gas-tragedy-extra-aid-to-help-just-42000-victims_1400833

- ↑ http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics/nation/Bhopal-case-US-Deputy-NSA-warns-of-chill-in-investment/articleshow/6333951.cms

- ↑ http://www.hindu.com/2010/08/21/stories/2010082164370100.htm

- ↑ http://www.ndtv.com/article/world/bhopal-gas-tragedy-is-a-closed-case-now-us-45797

References

Books and reports

- Preview of several more books at Google books. http://books.google.com/books?q=bhopal&btnG=Search+Books.

- Browning, Jackson (1993). Jack A. Gottschalk. ed (PDF). Union Carbide: Disaster at Bhopal. Crisis Response: Inside Stories on Managing Image Under Siege. Detroit. http://www.bhopal.com/pdfs/browning.pdf. "Union Carbide's former vice-president of health, safety and environmental programs tells how he dealt with the catastrophe from a PR point of view."

- Cassels, J. (1993). The Uncertain Promise Of Law: Lessons From Bhopal. University Of Toronto Press.

- ChouhanTR and others (1994, 2004). Bhopal: the Inside Story—Carbide Workers Speak Out on the World's Worst Industrial Disaster. US: The Apex Press. ISBN 1-891843-30-3. India: Other India Press ISBN 81-85569-65-7 Main author Chouhan was an operator at the plant. Contains many technical details.

- De Grazia A (1985). A Cloud over Bhopal,. Bombay: Popular Prakashan. http://www.grazian-archive.com/governing/bhopal/index.htm.

- Dhara VR (2000). The Bhopal Gas Leak: Lessons from studying the impact of a disaster in a developing nation.. US: Univ. of Massachusetts Lowell. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Health%20Effects%20&%20Epidemiology/Dhara%20Disseration%20Bhopal%20Disaster.pdf. Doctoral thesis.

- Doyle, Jack (2004). Trespass Against Us. Dow Chemical & The Toxic Century. US: Common Courage Press. ISBN 1-56751-268-2. http://www.trespassagainstus.com/index.php. A story of how one company's chemical prducts and byproducts have damaged public health and the environment. 466 pages.

- D'Silva, Themistocles (2006). The Black Box of Bhopal: A Closer Look at the World's Deadliest Industrial Disaster. Victoria, B.C.: Trafford. ISBN 1-4120-8412-1. Review Written by a retired former employee of UCC who was a member of the investigation committee that reproduced the tank residue and determined the true cause of the incident. Includes several original documents including correspondence between UCIL and the Ministries of the Government of India.

- Eckerman, Ingrid (2001) (PDF). Chemical Industry and Public Health—Bhopal as an example. http://www.lakareformiljon.org/images/stories/dokument/2009/bhopal_gas_disaster.pdf. Essay for MPH. A short overview, 57 pages, 82 references.

- Eckerman, Ingrid (2005). The Bhopal Saga—Causes and Consequences of the World's Largest Industrial Disaster. India: Universities Press. ISBN 81-7371-515-7. http://www.eckerman.nu/default.cfm?page=The%20Bhopal%20Saga. Preview Google books All known facts 1960s – 2003, systematized and analyzed. 283 pages, over 200 references.

- Fortun, Kim (2001). Advocacy after Bhopal. Environmentalism, Disaster, New Global Orders. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-25720-7. Preview Google books

- de Grazia, Alfred (1985). A Cloud over Bhopal—Causes, Consequences and Constructive Solutions. ISBN 0-940268-09-9. http://www.grazian-archive.com/governing/bhopal/Publishers%20Note.html. "The first book on the Bhopal disaster, written on-site a few weeks after the accident."

- Hanna B, Morehouse W, Sarangi S (2005). The Bhopal Reader. Remembering Twenty Years of the World's Worst Industrial Disaster. US: The Apex Press. ISBN 1-891843-32-X USA, 81-85569-70-3 India. Reprinting and annotating landmark writing from across the years.

- Jasanoff, Sheila ed. (1994). Learning from Disaster. Risk Management After Bhopal. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 081221532X, 9780812215328. 291 pages. Preview Google books

- Johnson S, Sahu R, Jadon N, Duca C (2009). Contamination of soil and water inside and outside the Union Carbide India Limited, Bhopal. New Delhi: Centre for Science and Environment. In Down to Earth

- Kalelkar AS, Little AD. (1998) (PDF). Investigation of Large-magnitude incidents: Bhopal as a Case Study.. http://bhopal.bard.edu/resources/documents/1988ArthurD.Littlereport.pdf. London: The Institution of Chemical Engineers Conference on Preventing Major Chemical Accidents

- Kulling P, Lorin H (1987). The Toxic Gas Disaster in Bhopal December 2–3, 1984. Stockholm: National Defence Research Institute. [In Swedish]

- Kurzman, D. (1987). A Killing Wind: Inside Union Carbide and the Bhopal Catastrophe. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kovel, J (2002). The Enemy of Nature: The End of Capitalism or the End of the World?. London: Zed Books.

- Labunska I, Stephenson A, Brigden K, Stringer R, Santillo D, Johnston P.A. (1999) (PDF). The Bhopal Legacy. Toxic contaminants at the former Union Carbide factory site, Bhopal, India: 15 years after the Bhopal accident. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Environmental%20Health/Greenpeace%20Bhopal%20Report.pdf.Greenpeace Research Laboratories, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter UK

- Lapierre, Dominique; Moro, Javier (2001). Five Minutes Past Midnight in Bhopal. New York, NY: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-53088-3. A novel, based on facts, that describes the development from the 1960s to the disaster itself. Very thrilling.

- Mitchel, James (1996). The long road to recovery: Community responses to industrial disaster. Tokyo and New York: United Nations University Press. ISBN 92-808-0926-1. http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu21le/uu21le00.htm#Contents.

- Singh, Moti (2008). Unfolding the Betrayal of Bhopal Gas Tragedy. Delhi, India: B.R. Publishing Corporation. ISBN 8176466220. The chief coordinator of rescue operations at the district level writes rather critically on how the administration and bureaucracy functioned after the disaster.

- Shrishti (2002). Toxic present—toxic future. A report on Human and Environmental Chemical Contamination around the Bhopal disaster site. Delhi: The Other Media.

- Stringer R, Labunska I, Brigden K, Santillo D. (2002) (PDF). Chemical Stockpiles at Union Carbide India Limited in Bhopal: An investigation. Greenpeace Research Laboratories. http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/international/press/reports/chemical-stockpiles-at-union-c.pdf.

- Varadarajan S et al. (1985). Report on Scientific Studies on the Factors Related to Bhopal Toxic Gas Leakage. New Delhi: Indian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research.

- Weir D (1987). The Bhopal Syndrome: Pesticides, Environment and Health. San Francisco: Sierra Club Books. ISBN 0871567180.

- Willey RJ, Hendershot DC, Berger S (2006). The Accident in Bhopal: Observations 20 Years Later. Orlando, Florida, USA: AIChE. http://www.aiche.org/uploadedFiles/CCPS/About/Bhopal20YearsLater.pdf.

- The Trade Union Report on Bhopal. Geneva, Switzerland: ICFTU-ICEF. 1985. http://www.bhopal.net/oldsite/documentlibrary/unionreport1985.html.

Articles and papers

- See also "International Medical Commission on Bhopal". http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Medical_Commission_on_Bhopal.

- "Health and Epidemiology Papers About the Bhopal Disaster". http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications.

- Bisarya RK, Puri S (2005). "The Bhopal Gas Tragedy - a Perspective". Journal of Loss Prevention in the process industry 18: 209–212. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2005.07.006. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TGH-4H21R3C-1/2/922a6ed2ebad15a178dea4a26daa0683.

- "Bhopal - the company's report, based on the Union Carbide Corporation's report, March 1985". Loss Prevention Bulletin. Rugby, UK.: IChemE,. 1985. http://cms.icheme.org/mainwebsite/resources/document/063bhopal.pdf.

- Broughton E (10 May 2005). "The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: A review". Environmental Health 4 (1): 6 pages. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-4-6. PMID 15882472. PMC 1142333. http://www.ehjournal.net/content/4/1/6.

- Chouhan TR (2005). "The Unfolding of Bhopal Disaster". Journal of Loss Prevention in the process industry 18: 205–208. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2005.07.025. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TGH-4H2G8YH-1/2/2f70debf0a05a3303428303074800554.

- Dhara, V. Ramana; Dhara, Rosaline (Sept/October 2002). "The Union Carbide disaster in Bhopal: A review of health effects" (reprint). Archives of Environmental Health. pp. 391–404. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Health%20Effects%20&%20Epidemiology/Health%20Effects%20Review%20articles/Health%20Effects%20Review%20AEH.pdf.

- Dhara VR, Gassert TH (September 2005). "The Bhopal gas tragedy: Evidence for cyanide poisoning not convincing". Current Science 89 (6): 923–5. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Toxicology/Current%20Science%20article%20&%20critique/Current%20Science%20critique%20Gassert%20Dhara%20&%20Sriramachari%20response.pdf.

- Dinham B, Sarangi S (2002). "The Bhopal gas tragedy 1984 - ? The evasion of corporate responsibility". Environment&Urbanization. pp. 89–99. http://www.docstoc.com/docs/42335332/The-Bhopal-gas-tragedy-1984-to-The-evasion-of.

- D'Silva TDJ, Lopes A, Jones RL, Singhawangcha S, Chan JK (1986). "Studies of methyl isocyanate chemistry in the Bhopal incident". J. Org. Chem. 51 (20): 3781–3788. doi:10.1021/jo00370a007.

- Eckerman, Ingrid (2005). "The Bhopal gas leak: Analyses of causes and consequences by three different models.". Journal of Loss Prevention in the process industry 18: 213–217. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2005.07.007. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6TGH-4GWC0T0-7&_user=99318&_coverDate=11%2F30%2F2005&_alid=1193044136&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_cdi=5255&_sort=r&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=1&_acct=C000007678&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=99318&md5=34c0e3b6b93cd1ef9dd2d5f0f6e11788.

- Eckerman, Ingrid (2006). "The Bhopal Disaster 1984 – working conditions and the role of the trade unions." (PDF). Asian Pacific Newsletter on occupational health and safety. pp. 48–49. http://www.ttl.fi/NR/rdonlyres/AF130282-A0AB-4439-8E3C-AFF55CDEF59F/0/AsianPacific_Nwesletter22006.pdf.

- Gassert TH, Dhara VR, (Sep 2005.). "Debate on cyanide poisoning in Bhopal victims." (PDF). Current Science. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Toxicology/Current%20Science%20article%20&%20critique/Current%20Science%20critique%20Gassert%20Dhara%20&%20Sriramachari%20response.pdf.

- Jayaraman N. "Bhopal: Generations of Poison". http://www.corpwatch.org/article.php?id=15485. CorpWatch, December 2, 2009

- Jasanoff, Sheila (2007). "Bhopal's Trials of Knowledge and Ignorance". Isis 98: 344–350. doi:10.1086/518194. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/518194.

- Katrak H (2010). "Provision of health care for Bhopal survivors". Pesticides News 87 (March 2010): 20–23.

- Khurrum MA, S Hafeez Ahmad S (1987). "Long term follow up of ocular lesion of methyl-isocyanate gas disaster in Bhopal". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology 35 (3): 136–137. PMID 3507407. http://www.ijo.in/article.asp?issn=0301-4738;year=1987;volume=35;issue=3;spage=136;epage=137;aulast=Khurrum.

- Lakhani N (2009-11-29). "Bhopal: The victims are still being born". The Independent (London). http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/bhopal-the-victims-are-still-being-born-1830516.html. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- Lepowski, W. "Ten Years Later: Bhopal". Chemical and Engineering News, 19 December 1994.

- McTaggart U. "Dioxin, Bhopal and Dow Chemical". http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/555. Solidarity ATC 106, September–October 2003

- Mishra PK, Dabadghao S, Modi1 GK, Desikan P, Jain A, Mittra I, Gupta D, Chauhan C, Jain SK, Maudar KK (2009). "In utero exposure to methyl isocyanate in the Bhopal gas disaster: evidence of persisting hyperactivation of immune system two decades later". Occupational and Environmental Medicine 66 (4): 279. doi:10.1136/oem.2008.041517. PMID 19295137. http://oem.bmj.com/content/66/4/279.extract.

- Naik SR, Acharya VN, Bhalerao RA, Kowli SS, Nazareth HH, Mahashur AA, Shah SS, Potnis AV, Mehta AC (1986). "Medical survey of methyl isocyanate gas affected population of Bhopal. Part I. General medical observations 15 weeks following exposure". Journal of Post-Graduate Medicine 32 (4): 175–84. PMID 0003585790. http://www.jpgmonline.com/article.asp?issn=0022-3859;year=1986;volume=32;issue=4;spage=175;epage=84;aulast=Naik.

- Naik SR, Acharya VN, Bhalerao RA, Kowli SS, Nazareth HH, Mahashur AA, Shah SS, Potnis AV, Mehta AC (1986). "Medical survey of methyl isocyanate gas affected population of Bhopal. Part II. Pulmonary effects in Bhopal victims as seen 15 weeks after M.I.C. exposure.". Journal of Post-Graduate Medicine 32 (4): 185–91. PMID 0003585791. http://www.jpgmonline.com/article.asp?issn=0022-3859;year=1986;volume=32;issue=4;spage=185;epage=91;aulast=Naik.

- Peterson M.J. "Case study: Bhopal Plant Disaster". Science, Technology & Society Initiative, University of Massachusetts Amherst. http://www.umass.edu/sts/ethics/bhopal.html.

- Ranjan N, Sarangi S, Padmanabhan VT, Holleran S, Ramakrishnan R, Varma DR (2003). Methyl Isocyanate Exposure and Growth Patterns of Adolescents in Bhopal "Methyl Isocyanate Exposure and Growth Patterns of Adolescents in Bhopal Methyl Isocyanate Exposure and Growth Patterns of Adolescents in Bhopal". JAMA (14). http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/290/14/1856 Methyl Isocyanate Exposure and Growth Patterns of Adolescents in Bhopal.

- Rice, Annie; ILO. "Bhopal Revisited—the tragedy of lessons ignored" (PDF). Asian Pacific Newsletter on occupational health and safety. pp. 46–47. http://www.ttl.fi/NR/rdonlyres/AF130282-A0AB-4439-8E3C-AFF55CDEF59F/0/AsianPacific_Nwesletter22006.pdf.

- Sriramachari S (2004). "The Bhopal gas tragedy: An environmental disaster" (PDF). Current Science 86: 905–920. http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/www.BhopalPublications/Toxicology/Current%20Science%20article%20&%20critique/Curr%20Science%20Bhopal%20article%20Sriramachari.pdf.

- Sriramachari S (2005). "Bhopal gas tragedy: scientific challenges and lessons for future". Journal of Loss Prevention in the process industry 18: 264–267. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2005.06.007. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6TGH-4GTW8RJ-1/2/367c60ca972ec8fde9ad2d3c1234e01c.

- Toogood C (2010). "Toxic groundwater – Bhopal's second disaster". Pesticide News 87 (March 2010).

Governmental institutions

- Health Effects of the Toxic Gas Leak from the Union Carbide Methyl Isocyanate Plant in Bhopal. Technical report on Population Based Long Term, Epidemiological Studies (1985–1994). Bhopal Gas Disaster Research Centre, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal (2003?) Contains the studies performed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)

- An Epidemiological Study of Symptomatic Morbidities in Communities Living Around Solar Evaporation Ponds And Behind Union Carbide Factory, Bhopal. Department of Community Medicine, Gandhi Medical College, Bhopal (2009)

- At A Glance. Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief & Rehabilitation 1985–2009. Bhopal Gas Tragedy Relief & Rehabilitation Department, Bhopal (2009)

- "Cr. Case No. 8460/1996". http://www.cbi.gov.in/whats_new/bhopalgas_judgement.pdf. The verdict in the Court of the Chief Juidicial Magistrate Bhopal MP. Date of Institution 01.12.1987. Delivered on 07, June 2010.

Union Carbide Corporation

- Methyl Isocyanate. Union Carbide F-41443A – 7/76. Union Carbide Corporation, New York (1976)

- Carbon monoxide, Phosgene and Methyl isocyanate. Unit Safety Procedures Manual. Union Carbide India Limited, Agricultural Products Division: Bhopal (1978)

- Operating Manual Part II. Methyl Isocyanate Unit. Union Carbide India Limited, Agricultural Products Division (1979).

- Bhopal Methyl Isocyanate Incident. Investigation Team Report. Union Carbide Corporation, Danbury, CT (1985).

- Presence of Toxic Ingredients in Soil/Water Samples Inside Plant Premises. Union Carbide Corporation, US (1989)

Dow Chemical

- Stockholder Proposal on Bhopal 2007. http://www.dow.com/financial/2007prox/161-00662.pdf. In Notice of the Annual Meeting of Stockholders to be held on Thursday, May 10, 2007 (Agenda item 4, pp 39–41)

- Annual Meeting Final Voting Results. http://www.dow.com/corpgov/pdf/20070510_voting.pdf. May 10, 2007

Mixed

- "Bhopal Disaster". Trade Environmental Database. TED case studies no. 233, American University, Washington (1 Nov 1997). http://www.american.edu/ted/bhopal.htm.

- "Bhopal Papers. Conference Announcement and Call for Papers". http://webdrive.service.emory.edu/users/vdhara/papers.htm. A collection of different articles and papers concerning the Bhopal disaster.

- Three part series on Horrors of Bhopal Gas Tragedy

- "Bibliography on Bhopal disaster". http://www.alyssaalappen.org/2002/12/04/bibliography-on-bhopal-disaster/. A condensed list of books, reports, and articles on the Bhopal disaster and related issues.

- "Chemical Terrorism Fact Sheet: Methyl Isocyanate." (PDF). http://bioterrorism.slu.edu/pulmonary/quick/methyliso.pdf. CSB&EI, Saint Louis University School of Public Health, US

- "Unproven technology". Bhopal.net (14 Nov 2002). http://www.bhopal.net/oldsite/unproventechnology.html.

- "Clouds of injustice. Bhopal disaster 20 years". http://www.amnesty.org/en/library/info/ASA20/015/2004/en. Amnesty International, London (2004) Report (pdf).

- "No more Bhopals". http://old.studentsforbhopal.org/Resources.htm. Contains original documents and categorizes resources by subject.

- The Bhopal Memory Project Material from UCC, the trade union and other original material has been scanned and can be found here.

- "Subterranean Leak". http://www.downtoearth.org.in/webexclusives/story1.htm. Down to Earth Dec 1, 2009.

- Fighting for Our Right to Live. Bhopal: Chingari trust. 2008. Chingari Trust works with disabled children.

- "Charter on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights" (PDF). http://web.archive.org/web/20071015132925/http://www.pan-uk.org/Internat/indhaz/Charter.pdf. Permanent Peoples' Tribunal on Industrial Hazards and Human Rights, 1996, adopted after the session in Bhopal, 1992.

Contamination of site

- A Report on Mercury Contamination of Groundwater near the Union Carbide Factory at Bhopal. Peoples' Science Institute, Dehra Doon (2001)

- "Chemical Stockpiles at Union Carbide India Limited in Bhopal: an investigation". http://www.greenpeace.org/raw/content/international/press/reports/chemical-stockpiles-at-union-c.pdf. Greenpeace Research Laboratories, Technical note, 12/2002

- Foul Debris. The UCIL plant is still a health hazard. Down to Earth, Dec 15 (2003).

Presentations